Permit me to begin with a metaphorical (but true) tale about a chicken. In my early twenties, shortly after I started cooking for myself, I visited some relatives living on a farm in Denmark. Thinking I would prepare a meal for them, I brought along a recipe for one of the few dishes I had mastered: a simple chicken stir-fry.

My aunt offered to gather the ingredients. I knew something was terribly wrong when I headed for the kitchen to get started and she called out, “The chicken is in the sink; I plucked it for you. Will you be needing the neck?”

My stir-fry called for boneless, skinless chicken breast–you know, the kind that comes wrapped in cellophane. As far as I could see, the thing with its chopped neck still bleeding in the sink had nothing whatsoever to do with chicken. And so the meal I was supposed to cook for my family turned into the meal where I swallowed my pride, and my disgust, and scrubbed potatoes while my aunt cooked the chicken, laughing her head off.

Americans are notoriously in the dark about where their food comes from (although we Mainers know a bit more about farming than most). But Mainers can claim no intimacy with where electricity comes from. It’s true that we know something about hydroelectric dams, but we simply can’t imagine the realities of mining and processing coal – the raw power behind over half the nations’ electricity. Our electricity comes skinned, de-boned, and neatly wrapped in cellophane.

The real story about electricity is, I think, especially hard to fathom because what it delivers is so helpful, so bright and so clean. It’s light in the dark, it’s dishes that wash themselves, it’s ice in summer, and it’s live-saving medical equipment. It serves us quietly, with no fuss: just a tangle of wires and a mysterious monthly bill.

Why mysterious? Consider this: How many of us know what a kilowatt hour (kWh) is? How many can read an electric meter? How many know what our dehumidifiers cost to run? Or that some TVs can use as much electricity as a refrigerator?

Contrast this ethereal substance with gasoline. Like all self-respecting vices, gasoline lets you know that it’s nasty. It looks nasty. It stinks, it smogs, and it exacerbates our kids’ asthma. We must constantly refill it, we know exactly what we are paying for and how it will get used up. We know we are buying gas guzzlers when we buy them. Spilled oil is an environmental hazard, but what happens to spilled electricity?

We could stand to put some more thought into electricity. It costs the average Maine household $1,000 a year. Pocket change this is not, nor are the environmental impacts of generating it.

In the case of coal, the bleeding chicken in the sink this: coal-fired power plants are possibly the largest obstacle we face to avoiding catastrophic climate change. They are the biggest single contributor to carbon dioxide emissions, and the United States is poised to build more. Yet they are so damaging that, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, even one additional plant is of grave concern.

And who up here in Maine could imagine that the last few decades of mining coal in Appalachia has meant bulldozing and blasting the tops off hundreds of mountains (several ridges a week at the current rate), utterly devastating over a half million acres of forest, and burying over 1,000 miles of valley streams?

Single mines cover thousands of acres. Silos and impoundments holding back lakes of toxic sludge sit perched above hundreds of communities, and in one case, just 300 feet from an elementary school. Is that dangerous? Last month, a coal sludge impoundment ruptured in Tennessee, poisoning forests, rivers, and homes with more than a billion gallons of toxic goop.

Fortunately (or perversely, depending on your perspective), a lot of electricity is wasted without providing any service to anyone–curtailing this waste offers us some easy opportunities to dramatically reduce use.

Our own household, much to my surprise, was able to drop our electric usage by 25% with no significant investment of time, money, or hardship. We already had an efficient fridge, hung our laundry, turned off lights (mostly), and had efficient bulbs in our primary light fixtures. What else was there?

First, we gradually switched all our remaining bulbs to compact fluorescents, which use about 70% less energy.

Second, we plugged our TV/VCR and computer/printer/modem into two power strips that we turn off when not in use. Most home electronics draw small but significant amounts of energy even when turned off . Efficiency Maine reports that this “phantom load” slurps up 75% of the juice used by these gadgets.

Third, we became progressively more compulsive about turning off lights in unoccupied rooms.

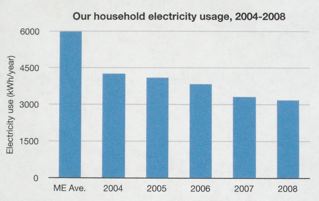

All we really did was to stop paying for electricity we were not benefitting from. Here is a graph of our power consumption. (The bar on the left is the average annual electricity use for a Maine household.) We now spend $160 a year less than we did in 2004, and our monthly bill is about $40.

Electricity in Maine comes largely from gas and oil-fired power plants, which, although not as bad as coal, both make significant contributions to global warming. For a few cents more per kWh, Mainers can buy electricity generated by emissions-free wind and hydro power through Maine Interfaith Power and Light (http://www.meipl.org/ or (207) 721-0444)).

What if Mainers led the way in reducing electricity demand and switching to renewables? We can, and should, inspire our fellow citizens to turn off the lights and change our light bulbs. And maybe school children in the poorest part of Appalachia can have some purple mountains majesty in their backyards rather than a new coal sludge silo.